Western Visayas Food Trip: The Historic Town of Silay

Silay was a place I wanted to visit for several reasons.

For one, I knew my favourite writer, Doreen Fernandez, spent her youth in Silay. And in her book “Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture”, Silay features prominently.

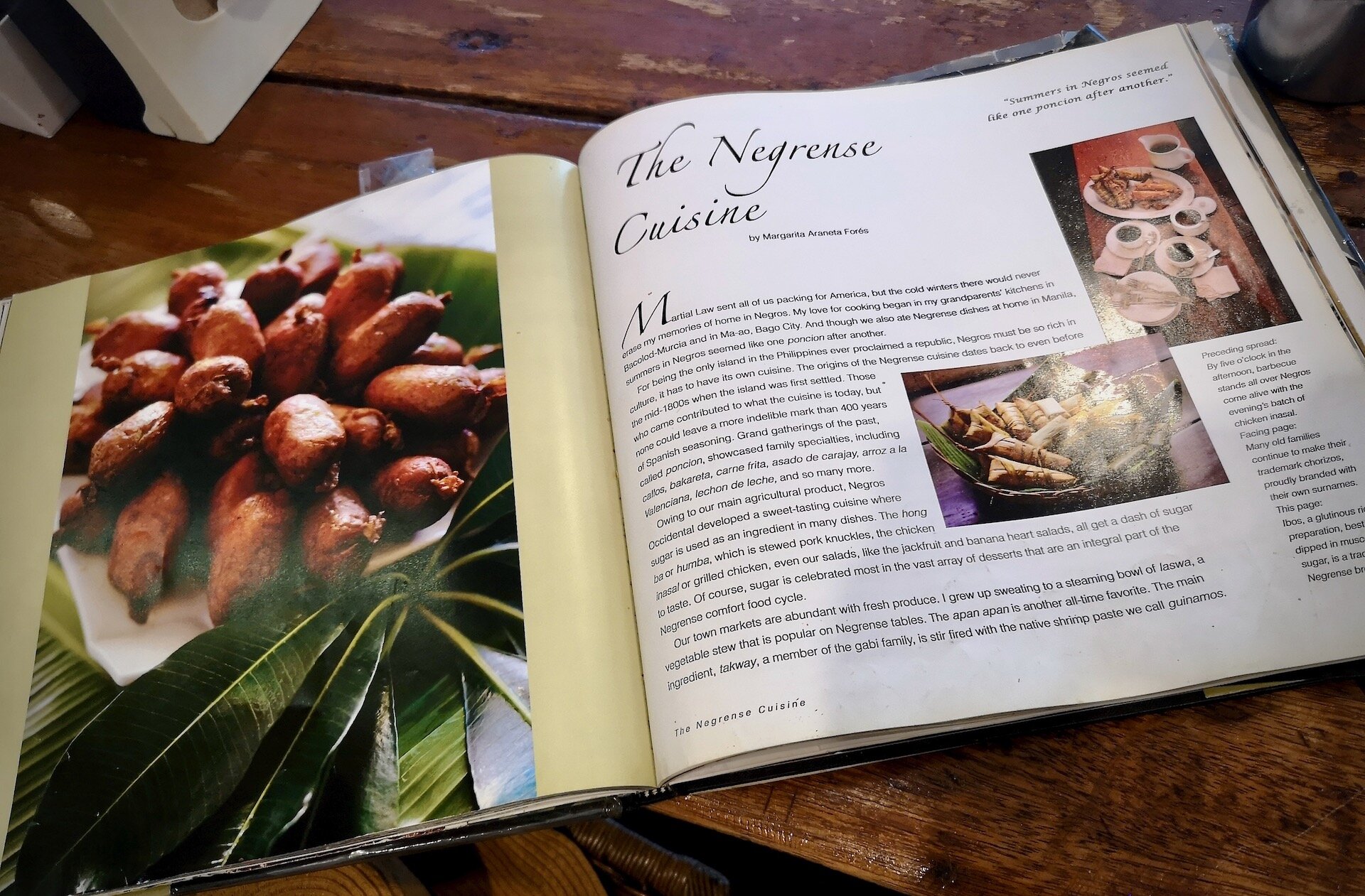

In an essay called “The Lumpia of Silay”, she writes, “it is incomparable, and the stuff of which Silaynon memories are made.” She starts an essay called “Sa Banwa sang Dulce: The Flavors of Negros” by saying: “Everywhere we go searching for Philippine regional food, our inquiries are answered with ‘oh, there’s nothing special about our food; it’s just like everywhere else’. And everywhere we’ve found them mistaken.” And in my favourite, an essay called “The Filipino Kitchen”, she writes about her childhood in a way that, to me, kind of feels like reading Anne of Green Gables. Like the scene where Anne first descends the road leading into Avonlea, I always feel a rush of excitement - and I guess, nostalgia, that tricky word, for a past that isn’t mine - with Doreen’s description of the bamboo and nipa palm “playhut” her father built in the yard:

“It had two rooms, a porch and a kitchen…we had kulon or palayok, pots of fired red clay, which turned black after use, and small wok-like karahay, clay skillets with handles. Although smaller than full-size, all could actually be used, and were authentic, having come from Barrio Guinhalaran, where the claypot craft had been flourishing for so long that the artisans can only say their fathers and grandfathers had been at it since their memories began.”

I’m like a fruit fly drawn to bananas with this kind of imagery. And frankly, it makes me wonder - what would it look like to really leverage the power of literature for promoting Philippine food tourism?

It’s also long-term goal of mine to visit as many of the bakeries featured in “Panaderia: Philippine Bread, Biscuit and Bakery Traditions”, and in Silay, there was El Ideal Bakery. It’s still in the ancestral home of the Locsin family, right on the main road, steps from the town plaza and church.

I’ve been fascinated with the names of their sweets and pastries. Like ‘angel cookies’, which allude to its main ingredient, hostia - the sacramental bread shared in Catholic mass. As nothing goes to waste, trimmings from producing the thin, light communion wafers (before they are ‘blessed’ by the local priest) make their way into El Ideal’s cookies. They make barquillos (thin, crisp layers of pastry rolled to look like a gigantic cigar), hojaldres (a round cookie made with puff pastry, dipped in sugar), galletas (a flat, buttery cookie), masa podrida (crumbly shortbread) and a host of cheekily-named pastries like lubid-lubid (braided like a rope), quinamonsil (shaped like a whole tamarind pod, but chunkier), isda-isda (think Goldfish crackers minus the cheese), and pacencia (one-bite eggy drop cookies) whose origin stories abound.

As I’m fairly certain machines make them these days, the only patience I risked losing was mine, when I eventually stood in front of El Ideal’s famous “aprador” trying to decide how my bags of biscuits - and which ones - I’d devour over the next week.

Silay is full of history, in its built structures, local culture, and food. During my visit, I stopped by Balay Negrense and the Hofilena House, and learned so much about the families from nearby Iloilo, who essentially built the Negros sugar industry.

Balay Negrense, in particular, is the ancestral home of Victor Fernandez Gaston, a sugar baron (with a French father) who owned many area estates, or haciendas, devoted entirely to sugarcane. Wandering the house itself is really like stepping back in time. Highly recommend a guided tour by one of the volunteer docents! I always opt for a tour, to bring everything you see into perspective.

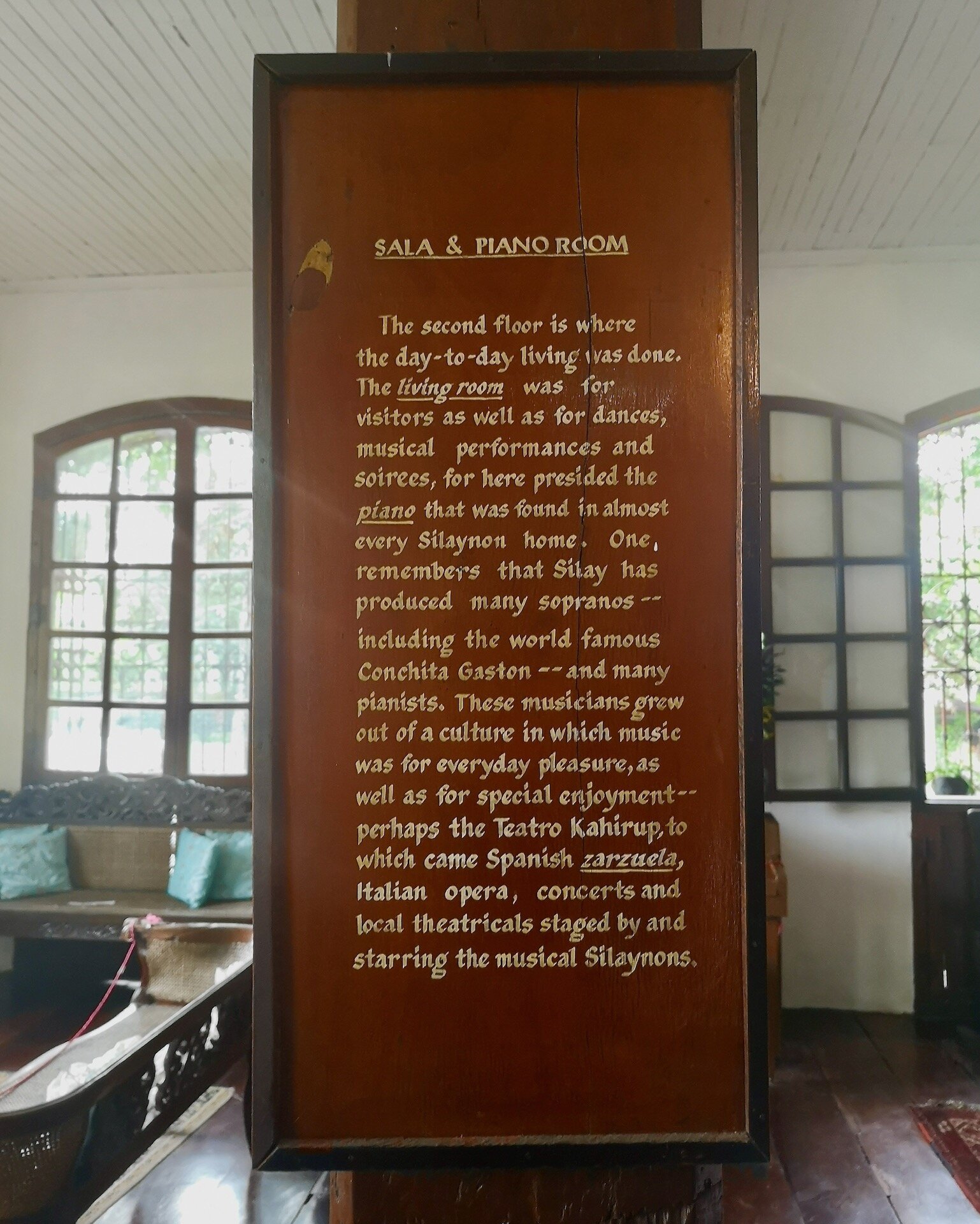

The left and right staircase, the carved partitions that separate rooms, and the intricate stitching on bed linens all date back to Silay’s peak in the late 19th century as what some call the ‘Paris of Negros’. Illustrious families, such as the Gastons, welcomed opera singers they met during travels abroad into their humble sala in Silay, to perform and, in essence, embed an appreciation of western art and culture far ahead of their neighbours in Bacolod and Iloilo, perhaps even of Manila.

And finally (I say this is a must), call the Hofilena Museum ahead to arrange a visit. If Ramon Hofilena - who currently lives in and cares for his family’s ancestral home - is around, I promise it’ll be a guided tour you won’t forget. The second floor is filled with artwork you wouldn’t believe resided in this mustard yellow house. What a collection!